When I get older, losing my hair, many years from now

When I get older, losing my hair, many years from now

Will you still be sending me a valentine, birthday greetings, bottle of wine?

If I’d been out ’til quarter to three, would you lock the door?

Will you still need me, will you still feed me when I’m sixty-four?

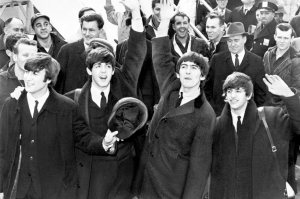

This Beatles tune became familiar to most Baby Boomers back in 1967. Some may still be asking these questions, but others are more worried that in their later years their medical symptoms will be misread by their physicians, attributed to normal aging instead of disease or treatable conditions.

“If you believe that your family doctor or specialist is ready to successfully handle your increasingly complex health care needs as you age, you are very likely wrong,” writes Bruce Brittain, a geriatric care consultant. Geriatrics is the medical specialty focusing on the health care needs of “the elderly” (frequently defined as those over the age of 64). The Baby Boomer generation began turning 65 in 2011, a slow-motion explosion which Brittain warns will create “77 million cranky old sex addicts with multiple medical complaints, worn out body parts but less hair.” His characterization may be debatable, but his conclusion isn’t: “There won’t be nearly enough trained geriatricians–and I’m talking about a huge gap because the number of geriatricians is shrinking–to provide appropriate care. The end result will be millions of misdiagnoses, over-medication (already a troubling problem), unnecessary and expensive procedures (likewise) and a reduced quality of life for millions of Boomers who would otherwise do quite nicely with correct care.”

There are currently about 7,600 certified geriatricians in the United States, representing just 1.2% of physicians in the country. That’s somewhere around one for every 2,600 Americans age 75 and older, according to the American Geriatrics Society. Ideally, there should be one for every 300.

Question #1: Why don’t more doctors in training become specialists in this field where the number of patients is growing exponentially?

First, it is not an especially lucrative specialty. A geriatric physician can expect to make about $200,000 per year, while other specialists average $400,000. Medicare and private insurers have established reimbursement caps, so many general practitioners briskly churn through a large caseload each day to maximize their income. To properly diagnose an elderly patient who presents with multiple complaints, a physician needs to spend time questioning and listening, something that many health care professionals avoid because it cuts down on their billable opportunities. In America, doctors are rewarded for procedures, not conversations.

Second, the curriculum at most U.S. medical schools treats geriatrics as an elective, not a required field of training. And, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, out of the 145 medical schools in the U.S., only 11 have a geriatric department. In Great Britain, every medical school has a department of geriatrics, as do one half of Japanese medical schools.

Medical school curricula have been slow to adapt and offer specialized instruction in the diagnosis and treatment of the aged. Dr. Adam Gordon, a consultant and lecturer in geriatrics at England’s Nottingham University Hospital, said, “Most medical school curriculums evolved in the last century, when the type of medicine we practiced was very different. And the way to teach doctors of old was to teach them about the heart, lung and liver and hope that they’ll somehow learn to join up the dots.” Yikes!

Question #2: What’s so different about treating older patients?

Would you take your two-year-old to your own physician? More than likely you would seek the expertise of a pediatrician. Advocates for the elderly say that geriatric medicine is as different from routine medicine as pediatrics is.

To begin with, older patients are likely to have multiple chronic conditions that overlap. A doctor may be challenged to assess which condition is implicated by a newly reported symptom. Elderly people often have multiple underlying disorders, such as hypertension or diabetes, that increase the potential for harm if a complaint is misdiagnosed. Even when a proper diagnosis has been made, the appropriate treatment of an elderly patient is likely to be different because older bodies absorb drugs more slowly and respond differently to certain protocols than younger bodies.

General physicians may dismiss some symptoms, regarding them as normal signs of aging. Things like confusion, unsteadiness, muscle weakness or gait oddities may be assumed to be typical characteristics of the elderly rather than signs of depression, nutrition or hygiene problems, or a urinary tract infection. Certain diseases are much more common among the elderly (diastolic heart failure, Alzheimer’s disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus) and may be more readily recognized by a geriatric specialist.

Conversely, doctors should take into account the natural effects of aging and not mistake pure aging for disease. For example, slow information retrieval is not dementia.

If a rose is a rose is a rose, isn’t a doctor a doctor? In a word, no. Dr. Joseph G. Ouslander, Founding Director of the Boca Institute for Quality Aging in Boca Raton, Florida, said, “I’ve worked with some truly outstanding physicians during my career but I’ve seen cases where they poison or misdiagnose their elderly patients due to ignorance of geriatric medicine.”

Question #3: Are there any solutions to the problem of the shortage of geriatric specialists?

Actually, South Carolina established an innovative program to attract more doctors with specialized training in geriatric medicine to our state. In 2005, the South Carolina General Assembly approved the first Geriatric Loan Forgiveness Program in the country. It offers up to $35,000 per year in loan forgiveness for those receiving training in an accredited geriatric fellowship, in exchange for their establishing and maintaining a geriatric or geropsychiatric practice in South Carolina for five consecutive years immediately following completion of fellowship training. With the average medical resident carrying a debt of $170,000, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges, this is a powerful incentive. Since 2006, 23 physicians have received loan forgiveness awards to establish practices in South Carolina, increasing the number of geriatricians in the state by over 50%.

Navigating safely through our later years is a challenge, and that includes finding a physician who correctly diagnoses and treats the physical and mental afflictions encountered in those years – one who takes the time necessary and who has the training and skills required and who doesn’t misread us when we’re 64 . . . or 74 . . . or 84 . . .

South Carolina Lawyer Blog

South Carolina Lawyer Blog